Over the last two years, a “double whammy” of high inflation and high interest rates has created economic turmoil and a cost-of-living crisis that has proved financially challenging to millions of people.

Happily, recent evidence suggests that inflation is now rapidly heading in the right direction, with the Office for National Statistics (ONS) confirming that the rate in the 12 months to October 2023 was just 4.6%, down from 6.7% in the previous month.

However, you’ll no doubt be well aware that interest rates are not following suit.

So, read about why that is the case, and when you might be able to expect the cost of borrowing to start coming down.

We’ve enjoyed a long period of low inflation and interest rates

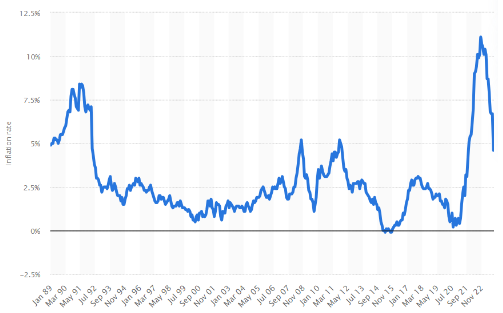

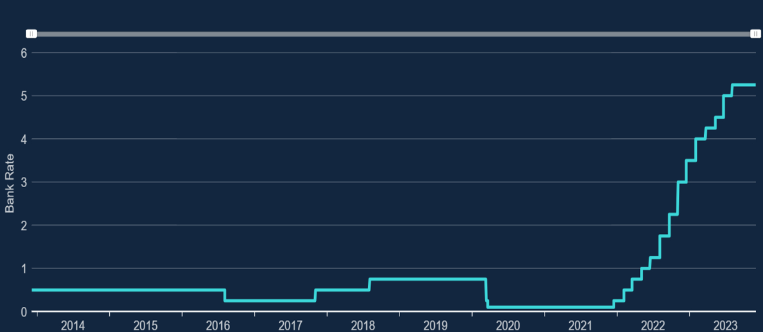

Even just a cursory glance at the two tables below makes it clear how we have become used to an almost unprecedented period of low interest rates and low inflation.

Source: Statista

Since the early 90s, inflation had stayed consistently at around 5% and under, until a conflation of events drove it quickly up to a level of 11.1% in October 2022, the highest figure for over 35 years.

At the same time, the Bank of England (BoE) base rate went below 1% in March 2009 in response to the financial crash, and stayed there until May 2022.

Source: Bank of England

Interest rates were raised to help control inflation

According to a House of Commons Library report, the rise in inflation was driven by three key factors:

- The pent-up demand for consumer goods after the pandemic and associated lockdowns.

- Supply chain disruption as distributors struggled to recover.

- Increasing energy and fuel prices driven primarily by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The BoE is tasked by the UK government to keep inflation at 2% a year. If inflation starts rising, economic orthodoxy suggests that the most effective way to suppress spending is to raise the cost of borrowing. As a result, prices should eventually start to fall.

As the BoE has control over the bank base rate, it was inevitable that it would use this financial instrument to try to bring inflation down. It did so on 14 consecutive occasions, starting from the end of 2021.

So, with inflation now back under some level of control, the natural expectation is that the BoE will start to reduce interest rates.

However, it’s likely that you may have to wait some time for this to happen.

The Bank of England will be cautious about cutting interest rates too quickly

As reported in Professional Adviser, the recent King’s speech made it clear that low inflation remains a key political priority.

As a result, the BoE is walking something of a tightrope between conflicting pressures. Reducing interest rates will ease the pressure on borrowers, but the banks will be very much aware that cutting rates too soon and too precipitously could prompt a consumer spending spree which would drive inflation back up again.

There are also external factors, which could also another rise in inflation, even if interest rates stay as they are.

A report in the Guardian confirmed BoE governor, Andrew Bailey’s contention that the recent fall in inflation was down to last year’s surge in energy prices not being repeated, rather than any easing of underlying price pressures.

He warned of a tough battle ahead to bring inflation back to the 2% target and suggested that there was no immediate prospect of an interest rate cut.

A This is Money report in November 2023 sought the opinion of several financial analysts regarding what would happen to interest rates in 2024. While there was no unanimity, the consensus would appear to be rates starting to come down, but at nowhere near the same rate that they went upAs the report puts it, “… rising like a rocket and falling like a feather”.

The “Table Mountain” analogy

Even when the BoE is comfortable enough to reduce rates, you are unlikely to enjoy such a prolonged period of low rates as you did before.

Much of the impetus for cheap borrowing between 2008 and 2020 was driven by quantitative easing (QE), as the BoE pumped money into the economy in the aftermath of the financial crash to stimulate economic activity.

The cost of the pandemic, and high inflation raising the cost of government borrowing, means a repeat of that is highly unlikely.

Indeed, according to a report in the Guardian, the BoE chief economist, Huw Pill, used the analogy of Table Mountain to describe the trajectory of interest rates, with a long period of rates levelling-off after a sudden rise.

You should ensure you’re getting the best rate on your savings

At the present time, we are experiencing a rare scenario of top savings rates being higher than the rate of inflation.

For example, according to Moneyfacts, the best two-year fixed-rate offer is currently 5.4%, well above the current inflation rate of 4.6% (as of 5 December 2023).

This creates an advantageous situation as, if the interest rate on your savings is higher than inflation, the real interest rate is positive, and the overall purchasing power of your savings actually increases.

As a result, it can make sense to ensure you are getting the best possible rate on any money you have in savings.

However, this may not be the best long-term option for money you’ll be leaving invested for a period of five years or more, as evidence typically shows that you will get better long-term returns by investing in shares and investment funds rather than in a standard savings account.

Get in touch

If you’d like to talk about any aspect of your financial planning, please get in touch with us.

Please note

The value of your investment can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount you invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

This article is for information only. Please do not solely rely on anything you have read in this article and ensure that you conduct your own research to ensure any actions you may take are suitable for your circumstances.

All contents are based on our understanding of HMRC legislation, which is subject to change.